Jay-z - Programming Your Culture lyrics

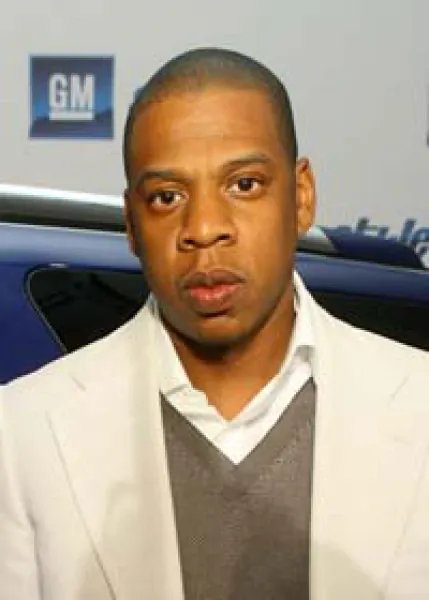

"I do this for my culture To let them know what a n***a look like when a n***a in a Roadster Show them how to move in a room full of vultures Industry is shady, it needs to be taken over Label owners hate me, I'm raising the status quo up I'm overcharging n***as for what they did to the Cold Crush" —Jay-Z, Izzo (H.O.V.A.) Ask 10 founders about company culture and what it means and you'll get 10 different answers. It's about office design, it's about screening out the wrong kinds of employees, it's about values, it's about fun, it's about alignment, it's about finding like-minded employees, it's about being cult-like. So what is culture? Does culture matter? If so, how much time should you spend on it? Let's start with the second question first. The primary thing that any technology startup must do is build a product that's at least 10 times better at doing something than the current prevailing way of doing that thing. Two or three times better will not be good enough to get people to switch to the new thing fast enough or in large enough volume to matter. The second thing that any technology startup must do is to take the market. If it's possible to do something 10X better, it's also possible that you won't be the only company to figure that out. Therefore, you must take the market before somebody else does. Very few products are 10X better than the competition, so unseating the new incumbent is much more difficult than unseating the old one. If you fail to do both of those things, your culture won't matter one bit. The world is full of bankrupt companies with world-cla** cultures. Culture does not make a company. So, why bother with culture at all? Three reasons: 1. It matters to the extent that it can help you achieve the above goals. 2. As your company grows, culture can help you preserve your key values, make your company a better place to work and help it perform better in the future. 3. Perhaps most importantly, after you and your people go through the inhuman amount of work that it will take to build a successful company, it will be an epic tragedy if your company culture is such that even you don't want to work there. Creating a company culture In this post, when I refer to company culture, I am not referring to other important activities like company values and employee satisfaction. Specifically, I am writing about designing a way of working which will: • Distinguish you from competitors • Ensure that critical operating values persist such as delighting customers or making beautiful products • Help you identify employees that fit with your mission Culture means lots of other things in other contexts, but the above will be plenty to discuss here. When you start implementing your culture, keep in mind that most of what will be retrospectively referred to as your company's culture will not be designed in, but will evolve over time based on the behavior of you and your early employees. As a result, you will want to focus on a small number of cultural design points that will influence a large number of behaviors over a long period of time. In Jim Collins' ma**ively successful book Built to Last, he wrote that one of the things that long lasting companies he studied have in common is a “cult-like culture”. I found this description to be confusing because it seems to imply that as long as your culture is weird enough and you are rabid enough about it, you will succeed on the cultural front. That's related to the truth, but not actually true. In reality, Collins was right that a properly designed culture often ends up looking cult-like in retrospect, but that's not the initial design principle. You needn't think hard about how you can make your company seem bizarre to outsiders. However, you do need to think about how you can be provocative enough to change what people do every day. Ideally, a cultural design point will be trivial to implement, but will have far reaching behavioral consequences. Key to this kind of mechanism is shock value. If you put something into your culture that is so disturbing that it always creates a conversation, it will change behavior. As we learned in The Godfather, ask a Hollywood mogul to give someone a job and he might not respond. Put a horse's head in his bed and unemployment will drop by one. Shock is a great mechanism for behavioral change. Here are three examples: Desks made out of doors – Very early on, Jeff Bezos, founder and CEO of Amazon.com, envisioned a company that made money by delivering value to rather than extracting value from its customers. In order to do that, he wanted to be both the price and customer service leader for the long run. You can't do that if you waste a lot of money. Jeff could have spent years auditing every expense and raining hell on anybody who overspent, but he decided to build frugality into his culture. He did it with an incredibly simple mechanism: all desks at Amazon.com for all time would be built by buying cheap doors from The Home Depot and nailing legs to them. These door desks are not great ergonomically nor do they fit with Amazon.com's $100+ billion market capitalization, but when a shocked new employee asks why she must work on a makeshift desk constructed out of random Home Depot parts, the answer comes back with withering consistency: “We look for every opportunity to save money so that we can deliver the best products for the lowest cost.” If you don't like sitting at a door, then you won't last long at Amazon. $10 per minute – When we started Andreessen Horowitz, Marc and I wanted the firm to treat entrepreneurs with great respect. We remembered how psychologically brutal the process of building a company was. We wanted the firm to respect the fact that in the bacon and egg breakfast of a startup, we were with the chicken and the entrepreneur was the pig: we were involved, but she was committed. We thought that one way to communicate respect would be to always be on time to meetings with entrepreneurs. Rather than make them wait in our lobby for 30 minutes while we attended to more important business like so many venture capitalists that we visited, we wanted our people to be on time, prepared and focused. Unfortunately, anyone who has ever worked anywhere knows that this is easier said than done. In order to shock the company into the right behavior, we instituted a ruthlessly enforced $10/minute fine for being late to a meeting with an entrepreneur. So, you are on a really important call and will be 10 minutes late? No problem, just bring $100 to the meeting and pay your fine. When new employees come on, they find this shocking, which gives us a great opportunity to explain in detail why we respect entrepreneurs. If you don't think entrepreneurs are more important than Venture Capitalists, we can't use you at Andreessen Horowitz. Move fast and break things – Mark Zuckerberg believes in innovation and he believes there can be no great innovation without great risk. So, in the early days of Facebook, he deployed a shocking motto: move fast and break things. Did the CEO really want us to break things? I mean, he's telling us to break things! A motto that shocking forces everyone to stop and think. When they think, they realize that if you move fast and innovate, you will break things. If you ask yourself, “Should I attempt this breakthrough? It will be awesome, but it may cause problems in the short term.” You have your answer. If you'd rather be right than innovative, you won't fit in at Facebook. Prior to figuring out the exact form of your company's shock therapy, be sure that your mechanism agrees with your values. For example, Jack Dorsey will never make his own desks out of doors at Square because at Square, beautiful design trumps frugality. When you walk into Square, you can feel how seriously they take design. Why dogs at work and yoga aren't culture Startups today do all kinds of things to distinguish themselves. Many great, many original, many quirky, but most of them will not define the company's culture. Yes, yoga may make your company a better place to work for people who like yoga. It may also be a great team-building exercise for people who like yoga. Nonetheless, it's not culture. It will not establish a core value that drives the business and help promote in perpetuity. It is not specific with respect to what your business aims to achieve. Yoga is a perk. Somebody keeping a pit bull in her cube may be shocking. However, the lesson learned—that animal lovers are welcome or that employees can live however they want—may be societal values, but they do not connect to your business in a distinguishing way. Every smart company values their employees. Perks are good, but they are not culture. The point of it all In How Andreessen Horowitz Evaluates CEOs, I described the CEO job as knowing what to do and getting the company to do what you want. Designing a proper company culture will help you get your company to do what you want in certain important areas for a very long time.